Earned Value Management: Fundamentals, Systems, and Formulas

Cost overruns have become a common reality among large-scale projects. The completion of the Access Oklahoma project (an endeavor aiming to build new turnpikes and fix existing ones), for example, was originally planned to cost $5 billion, but its final cost is projected to amount to $8.2 billion. That’s a 64% increase from its planned value.

No project manager wants to be at the helm of projects that stray off their course. When faced with these difficulties, project professionals rely on strong project management processes to resolve problems. Earned value management is one of these tried-and-true methods that can help project managers navigate any bumps in the road.

What is Earned Value Management?

Earned value management (EVM) is a project management methodology that integrates schedule, costs, and scope to measure project performance. Based on planned and actual values, EVM predicts the future and enables project managers to adjust accordingly.

In turn, Earned Value Management Systems (EVMS) refer to the software, processes, tools, and templates used for EVM.

Another important terminology used in this context is earned value analysis (EVA). EVA is a quantitative technique used to evaluate project performance by analyzing schedule and cost variances.

EVM uses EVA as one of its tools, but is larger in scope. While EVA stops with the compute portion, EVM is all about using that data in trends analysis and forecasting. EVM is a project management function—so it deals with both the data itself and the actions taken in light of that data.

The Origins of EVM

EVA, EVM, and EVMS have a fascinating origin story. In the 1960s, 35 criteria were drafted for the U.S. government’s contractor management systems to follow. Later in the 1990s, the American National Standard Institute (ANSI) and the Electronic Industries Association (EIA) developed these into 32 guidelines for EVMS, resulting in the ANSI/EIA 748 standard. For technology systems used in several U.S. government agencies such as the Department of Defense (DoD) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), this has now become the gold standard.

At the same time, the EIA 748 standard is not required to implement EVM. All those criteria and the rules around them have contributed to a perception that EVM is difficult and onerous. The good news is that EVM metrics are actually quite straightforward and your EVM process can be implemented with as much or as little rigor as your particular projects require.

Benefits of Earned Value Management

According to a detailed study by Fleming and Koppelman, once you’re 20% into a project, your current performance can be used to predict the future of the project with a plus or minus 10% deviation. This powerful predictive capability is made possible by EVM, making it one of the best project cost control measures available.

Earned value management is a powerful tool with many benefits, enabling you to:

- Map work with costs, reducing unknowns into quantifiable factors.

- Compare and benchmark the current status against the project baseline and identify critical paths.

- Create a data-based framework to take actions and make decisions for the future.

- Intervene fast and ahead of time (for example, you can tweak project scope and budgets, rollback functionalities, procure more resources, invest in better technologies, set customer expectations, pivot resources, etc.).

- Promote enhanced visibility and create accountability in stakeholders through clear metrics.

- Provide insight into the big picture at both project and portfolio levels.

Earned Value Management Core Concepts

EVM can be intimidating to some project managers, due to the many terminologies associated with it. So, let’s break this down into easy-to-digest smaller concepts first. We’ll also provide a list of the most important EVM formulas for reference below. Each of these concepts plays a key role in improving project performance.

Planned Value (PV)

Planned value is the budgeted cost for work scheduled (BCWS). PV varies based on the scope of work in consideration and the point where you’re at in the overall schedule.

PV = Total project cost * % of planned work

For example, let’s say, the PV for your 5-month project is $25,000:

PV for the complete project = $25,000

PV at 2 months = $25,000 * 40% = $10,000

You can also calculate PV for a time period, say, month 2 to month 4 = $25,000 * 60% = $15,000.

Actual Costs (AC)

Actual costs, also known as actual cost of work performed (ACWP), is relatively straightforward. If you are using a robust project cost management software, tracking actual costs should not be a challenge. However, it’s important to remember to include several hidden costs—material, resource, hardware, software licenses, overheads, etc.

You can look at AC cumulatively, accounting for all the activities done from the beginning of the project to date or over a specific time period.

In our example, let’s assume, AC at the end of 2 months = $15,000

Earned Value (EV)

Now, this is where EVM gets interesting. You’ve made a plan to complete a certain amount of work and budgeted accordingly. But, from experience, you know that there is bound to be some discrepancy from your estimate. At the end of 2 months, you may have planned to complete 40% of your work, but let’s say you only managed to finish 30%.

The question, then, is, what’s the budgeted cost for this work? EV, also referred to as budgeted cost for work performed (BCWP), gives you the answer.

In our example:

EV = Total project cost * % of actual work = $25,000 * 30% = $7,500

Variance Analysis

Planned value, actual cost, and earned value numbers are vital to variance calculations. At this point, the project manager wants to know how far off we are from the project baseline. This can be determined through schedule and cost variance.

Schedule Variance (SV)

Schedule variance is a quantitative indicator of your divergence from the initial planned schedule. A negative SV indicates that we are behind schedule, a positive SV indicates that we are ahead of schedule and zero means that we are exactly on schedule.

SV = EV – PV

In our example, SV at 2 months = $7,500 – $10,000 = -$2,500

SV% = (SV/PV) *100 = (-$2,500/$10,000) *100 = -25%

This implies that we are 25% behind schedule. It’s interesting to note that we aim to understand schedule, a time component, from the perspective of costs. To arrive at these costs though, we needed to know the scope of work planned and completed. This is how the three pillars—scope, time and cost come together in EVM.

Cost Variance (CV)

Cost variance is a quantitative indicator of your divergence from the initial planned budget. A negative CV indicates that we are over budget, a positive CV indicates that we are under budget and zero means that we are exactly on budget.

CV = EV – AC

In our example, CV at 2 months = $7,500 – $15,000 = -$7500

CV% = (CV/EV) *100 = (-$7,500/$7,500) *100 = -100%

This implies that we are 100% over budget.

Again, this is an instance of how scope, time and cost come together to give you a clear picture of where you currently stand in your project.

Performance Indexes

Another way of looking at project performance, apart from variance, is through indexes. Here again, we have two parameters—schedule and cost index.

Schedule Performance Index (SPI)

SPI gives a sense of project performance from a schedule perspective.

SPI = EV/PV; SPI > 1 indicates the project is ahead of schedule and SPI < 1 indicates the project is behind schedule. In our example, SPI = $7,500/$10,000 = 0.75, indicating the project is only going 75% as per the original plan or it’s 25% behind schedule.

Cost Performance Index (CPI)

CPI gives a sense of project performance from a cost perspective. CPI = EV/AC; CPI > 1 indicates the project is under budget and CPI < 1 indicates the project is over budget.

In our example, CPI = $7,500/$15,000 = 0.5, indicating the project expenditures are only at 50% of the plan.

Earned Value Management Formulas

Here’s a quick reference guide to the most important EVM formulas:

|

Metric |

Formula |

Description |

|

Planned Value (PV) |

PV = Planned % Complete x BAC |

The authorized budget assigned to scheduled work up to a specific point in time. Also known as Budgeted Cost for Work Scheduled (BCWS). |

|

Earned Value (EV) |

EV = Actual % Complete x BAC |

The value of work completed to date, expressed in terms of the approved budget. Also known as Budgeted Cost for Work Performed (BCWP). |

|

Actual Cost (AC) |

AC = Sum of Costs Incurred |

The actual cost incurred for the work completed. Also known as Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP). |

|

Cost Variance (CV) |

CV = EV - AC |

The amount of budget deficit or surplus at a given point in time. Indicates cost performance. |

|

Schedule Variance (SV) |

SV = EV - PV |

The amount of schedule deficit or surplus at a given point in time. Indicates schedule performance. |

|

Cost Performance Index (CPI) |

CPI = EV / AC |

A measure of cost efficiency on a project.

|

|

Schedule Performance Index (SPI) |

SPI = EV / PV |

A measure of schedule efficiency on a project.

|

|

Estimate at Completion (EAC) |

EAC = BAC / CPI or EAC = AC + (BAC - EV) |

The expected total cost of completing all work.

|

|

Estimate to Complete (ETC) |

ETC = EAC - AC |

The expected cost to finish all remaining work. |

|

Variance at Completion (VAC) |

VAC = BAC - EAC |

The difference between the Budget at Completion (BAC) and the Estimate at Completion (EAC). |

|

To-Complete Performance Index (TCPI) |

TCPI = (BAC - EV) / (BAC - AC) or TCPI = (BAC - EV) / (EAC - AC) |

The cost efficiency required to complete the project within a given budget or estimate.

|

Earned Value Management System Architecture

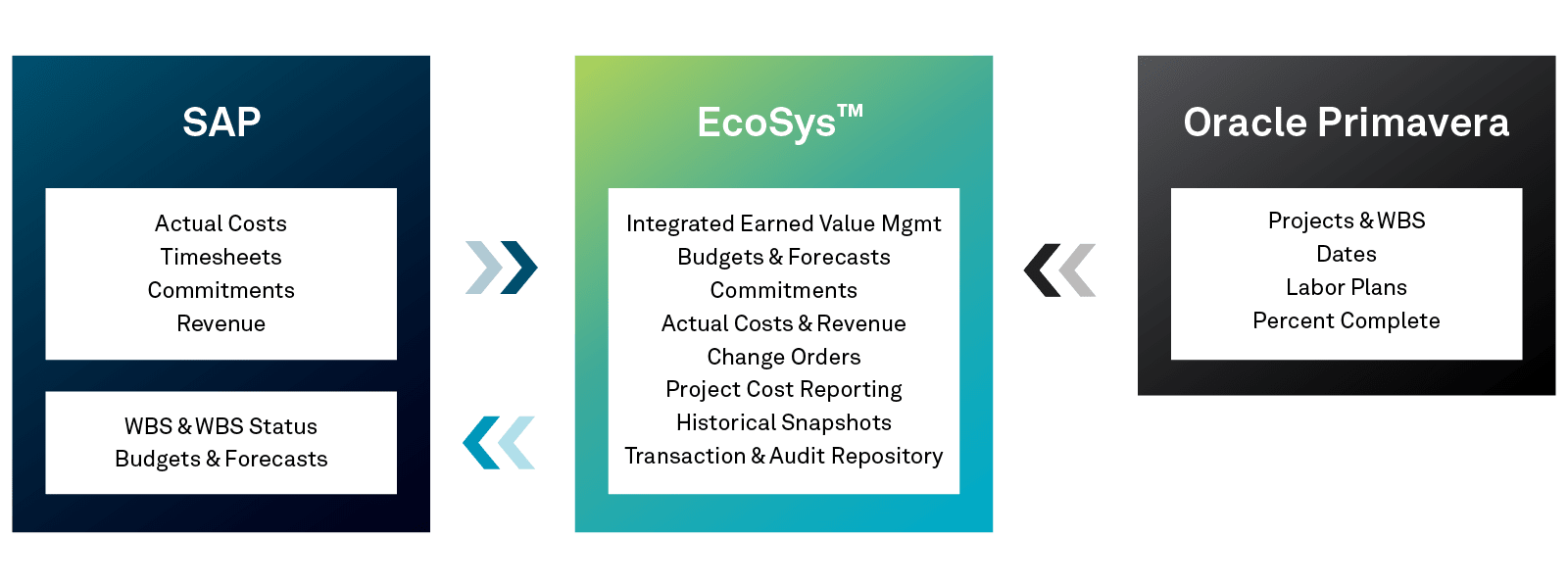

Here is a typical system landscape supporting EVM:

- The ERP system (SAP, JD Edwards, Oracle EBS, Baan or other) contains key information such as actual cost, timesheets, commitments, etc.

- The Enterprise Project Performance system (EcoSys) becomes the central platform and EVM engine. You can bring together key data from other systems. Then, you can perform key functions such as budgets, change management, progress measurement, earned value analysis, forecasts and reporting.

- The scheduling tool (Primavera P6, Ms Project, Safran or other) is the basis of key information. This includes information such as the WBS, activity codes, dates, resource allocation and percent complete.

Earned Value Management Process

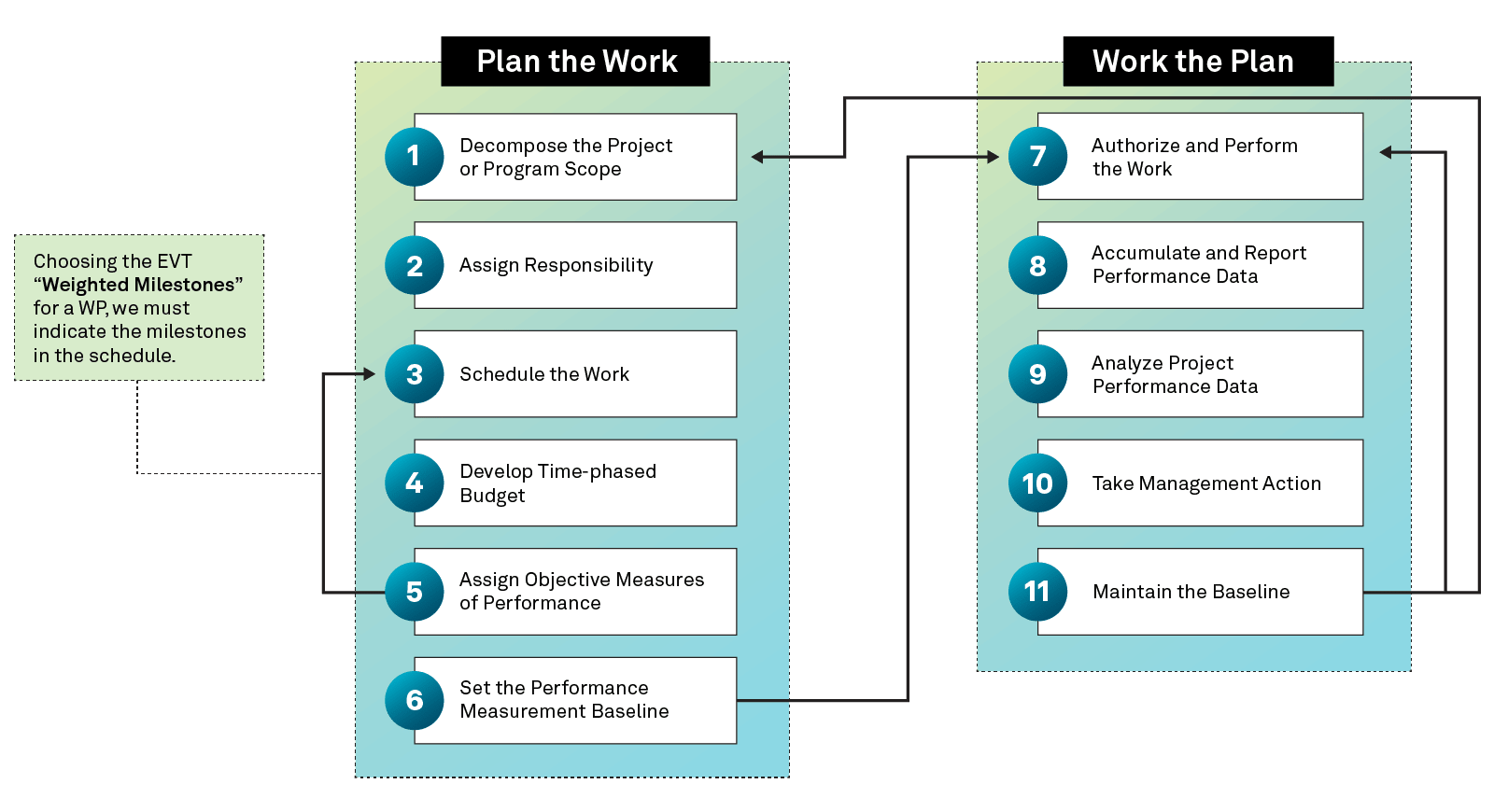

ISO 21508 provides guidance for practices of EVM in project and program management. It is applicable to any type of organization including public or private and any size or sector. It also applies to any type of project or program in terms of complexity, size or duration. The main processes are the following:

- Project planning processes (Plan the work) with the PMB as the final deliverable.

- Processes of execution of the plan (Work the plan) that generate the reports and support decision making.

5 Fundamentals of Earned Value Management

Earned value management is all about measuring and benchmarking against a well-defined plan. Therefore, you can only perform this in organizations with a certain key elements in place. The 32 guidelines defined under the EIA-748 standard discuss, in detail, the fundamental processes and systems for the implementation of EVM. These guidelines are outlined as part of five broad principles. But again, the level of detail and overhead to implement should vary based on factors including organizational maturity, project size and complexity and contractual requirements. Let’s review these principles.

1. Organization and Scope of Project

We start by identifying the ‘what’ element of the project with requirements collection and scope definitions. The five guidelines documented as part of this principle recommend us to create three important documents:

- Work breakdown structure (WBS): Create a WBS dividing high-level deliverables into smaller work packages. This graphical representation of the work we have set out to complete gives clarity on the scope.

- Organization breakdown structure (OBS): Create an OBS, a form of an organization chart, which shows the people, teams and departments that are involved in a project, along with their hierarchy, roles and responsibilities. OBS addresses the ‘who’ element.

- Responsibility assignment matrix (RAM): Interpose the WBS and OBS to create a RAM, defining exactly which task will be performed by whom. Each of these mappings or control accounts will be measured in future stages.

2. Planning, Scheduling, and Budgeting

The objective of the guidelines in this principle is to help define the project baseline in concrete terms. These are the parameters against which the project will be monitored and controlled throughout the lifecycle.

The WBS is a good starting point for the planning stage. We ensure that multiple activities are grouped under a single work package and multiple work packages are grouped under a single control account. Each account will have an account manager who will monitor its progress (in reality, the same person could manage multiple accounts).

At this point, we define the “when” element, defining both high- and low-level milestones and assigning clear due dates to each activity.

Then, we move on to time-phased budget allocation, apportioning the total budget at the level of each activity inside a work package. This includes costs, such as labor, material and subcontracting. We also assign methods of progress measurement to each work package, which will decide how EV will be calculated at a later point for a task-in-progress.

The sum of all budgeted work is called as the performance measurement baseline. Additionally, project managers allocate management reserves for unexpected scope increases.

3. Accounting for Actual Costs

A set of six guidelines discusses the process of cost calculation. The focus of this activity is simple—to measure the actual costs. But it’s important to have systems in place that can track costs at a work package level, otherwise it’ll be difficult to measure progress accurately. Also, it’s possible that you may be incurring/paying out the actual costs only a few months later, but a portion of it has to be allocated much earlier to calculate the earned value. To avoid these booking lags, the guidelines emphasize on accounting for accruals.

4. Analyzing and Reporting on Project Performance

The calculations of PV, EV, AC, along with variances and indexes are described in detail in this section with six guidelines. The idea is to consistently report these numbers such that team members, senior leaders, and customers have visibility into project progress.

But the focus is as much on identifying the corrective actions to be taken as the measurement against the baseline and reporting numbers. The guidelines recommend defining variance thresholds; when the cost performance reports indicate a threshold breach in a control account, one can drill down to spot the problematic tasks.

5. Revisions and Data Maintenance

The five guidelines under this section acknowledge that the project baseline is not rigid, especially when problem areas are uncovered in the middle of a project. But you cannot revise a baseline every time you overspend or there is a delay in a task. Some scenarios when the guidelines recommend revising a baseline are when there is an authorized change to the scope, cost or schedule of the project or when there is fluctuation in rates.

Creating change management and risk management plans, seeking necessary approvals and evaluating the need to dip into the management reserve are some of the activities that fall under this section.

Discover the Right EVM Solution for Your Projects

Earned Value Management (EVM) is one of the most precise techniques for project forecasting, making it invaluable for organizations aiming to enhance project performance. However, its complexity requires a robust Earned Value Management System (EVMS) to ensure successful implementation and scalability.

EcoSys provides a comprehensive EVMS platform that supports all levels of EVM, from basic project performance measures to full compliance with the EIA-748 standard. It includes features like control account definition, Work Breakdown Structure (WBS), and Organizational Breakdown Structure (OBS). EcoSys also integrates seamlessly with ERP, financial systems, scheduling tools, timesheets, and other enterprise solutions for tracking costs and resource utilization.

Visit these additional resources for more information on earned value management:

Product: EcoSys

Solutions: Earned Value Management, Project Controls & Project Management

Content: Adopting Right-Sized EVM to Drive Project Performance